Introduction

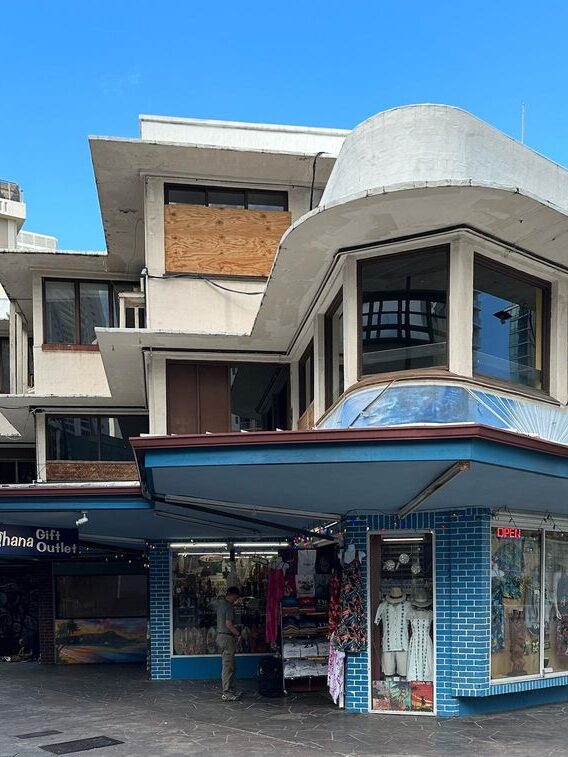

Dizengoff Center is more than just a shopping mall; it’s a landmark in Tel Aviv that has evolved alongside the city itself. Situated in the City Center at the intersection of Dizengoff Street and King George Street, the center is a symbol of urban dynamism, architectural innovation, and cultural integration. This essay explores the history, architecture, urban planning, and design of Dizengoff Center, and delves into some fascinating facts about its impact on the city.

Dizengoff Center, the first shopping center in Israel, has become a phenomenon, an icon, a city within a city. “The Center” is more than a shrine for consumption or a shopping place, for many people it’s a place they call “a home”.

History

Origins

Dizengoff Center’s history dates back to the early 1970s. It was the brainchild of Arieh Pincus, a businessman who envisioned a shopping and entertainment complex that would revitalize the city’s center. The project was ambitious, aiming to transform the relatively quiet Dizengoff Street into a bustling commercial hub.

Construction began in 1972, and the center officially opened its doors in 1977. The center was named after Meir Dizengoff, the first mayor of Tel Aviv, symbolizing a tribute to his vision for the city. The project faced several challenges, including financial difficulties and public skepticism, but Pincus’s determination saw it through to completion.

Architecture

Design and Style

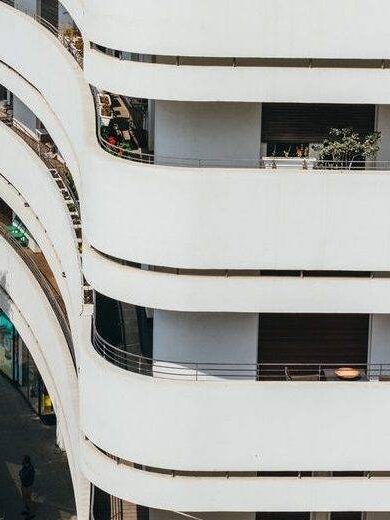

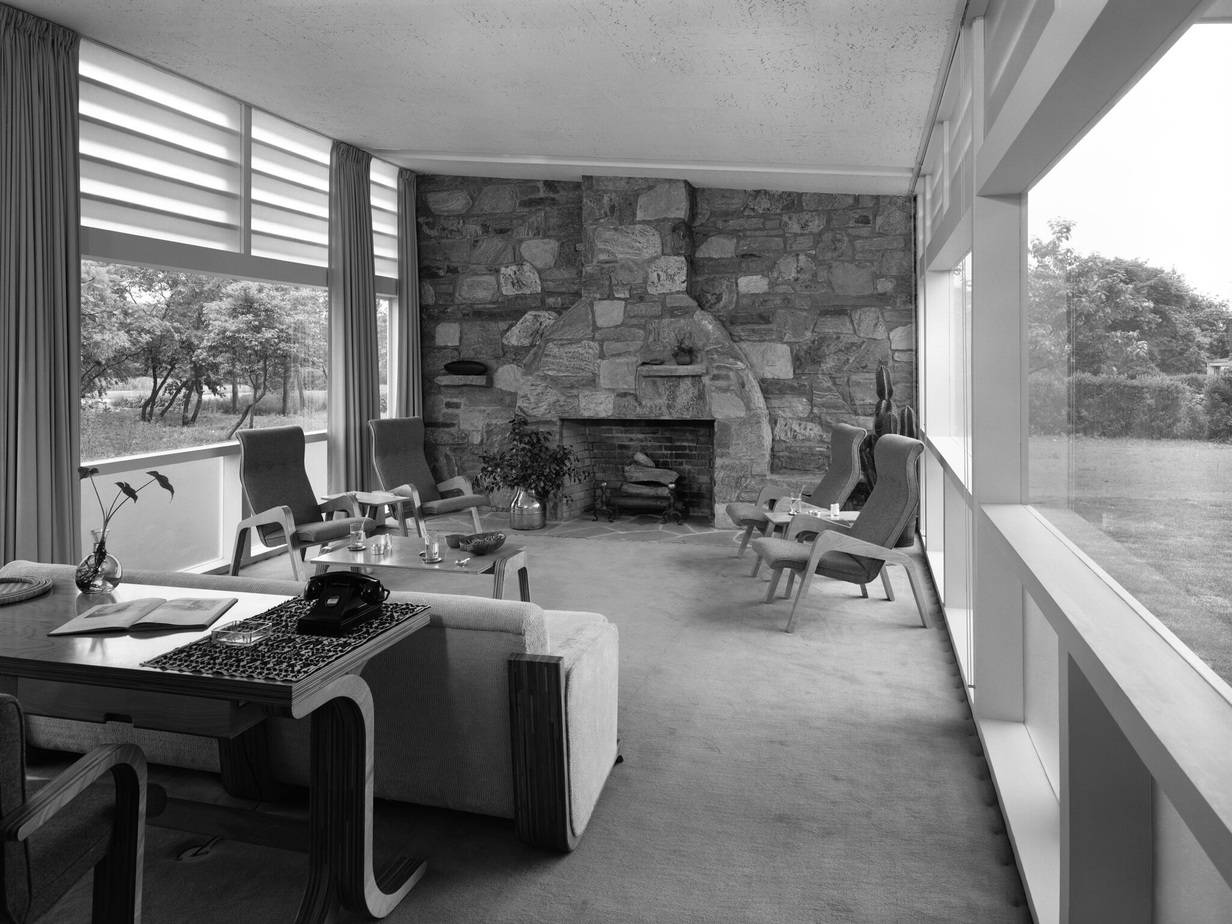

Dizengoff Center’s architecture is a unique blend of Brutalism and modernism, reflecting the prevailing styles of the 1970s. The architects behind the project, Yitzhak Yashar and Arieh Elhanani, designed the complex with a distinctive look characterized by its use of raw concrete and geometric forms. The center’s architecture was meant to convey a sense of solidity and modernity, aligning with the rapid development of Tel Aviv at the time.

One of the most notable features of Dizengoff Center is its labyrinthine layout. Unlike traditional malls with straightforward linear designs, Dizengoff Center’s layout is complex and multi-level, almost maze-like. This design choice was intentional, aiming to encourage exploration and discovery, as shoppers navigate through a network of interconnected corridors, passages, and bridges.

Key Architectural Elements

- Brutalist Aesthetics: The center’s raw concrete facade and utilitarian design elements are hallmarks of Brutalism. This architectural style, though often criticized for its stark appearance, was chosen for its durability and the sense of strength it imparts.

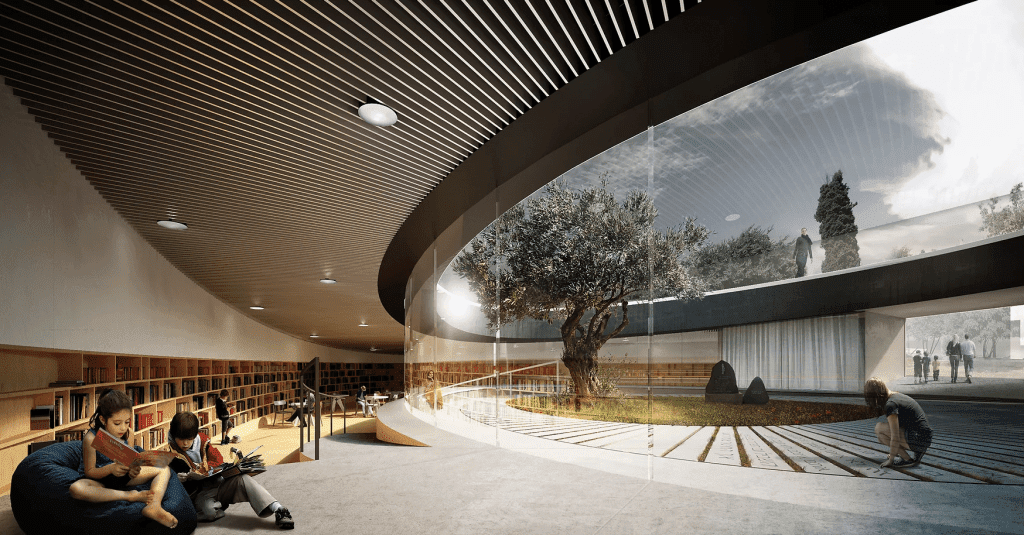

- Glass Atriums: The use of large glass atriums allows natural light to flood the interior spaces, creating an inviting atmosphere despite the Brutalist exterior.

- Interconnected Bridges: The bridges that connect different sections of the mall are both functional and symbolic, representing the interconnectedness of the urban environment.

Urban Plan

Integration with the City

Dizengoff Center was designed to be more than just a shopping destination; it was envisioned as an integral part of the urban fabric of Tel Aviv. The center’s location at a major intersection ensures its accessibility, making it a focal point for both residents and visitors.

The urban plan incorporated several elements to ensure seamless integration with the surrounding cityscape:

- Pedestrian Accessibility: Multiple entrances and exits connect the center to adjacent streets, facilitating easy pedestrian flow. This design encourages foot traffic from nearby neighborhoods and enhances the center’s role as a community hub.

- Public Spaces: The center includes several public spaces, such as plazas and courtyards, which serve as gathering spots for social activities and events.

- Mixed-Use Development: Dizengoff Center is not just a commercial space; it includes residential units, offices, and recreational facilities. This mixed-use approach enhances the center’s vibrancy and ensures a constant flow of people throughout the day and night.

Impact on Urban Development

The establishment of Dizengoff Center marked a significant shift in Tel Aviv’s urban development. Prior to its construction, the area was relatively underdeveloped. The center’s success spurred further development in the vicinity, leading to the emergence of new businesses, restaurants, and cultural venues.

The center also influenced urban planning trends in Tel Aviv, demonstrating the viability of mixed-use developments and the importance of integrating commercial spaces with public amenities. This approach has since been replicated in various projects across the city.

Design

Interior Design

The interior design of Dizengoff Center is as dynamic as its exterior architecture. The mall’s interior spaces are characterized by their eclectic mix of styles and influences, creating a vibrant and stimulating environment.

- Art Installations: The center frequently hosts art installations and exhibitions, showcasing the work of local and international artists. These installations add a cultural dimension to the shopping experience and reflect Tel Aviv’s artistic spirit.

- Thematic Zones: Different sections of the mall are designed with distinct themes, creating a sense of variety and novelty. This approach not only enhances the aesthetic appeal but also helps orient shoppers within the complex layout.

- Interactive Elements: Dizengoff Center includes several interactive elements, such as digital kiosks, play areas for children, and performance stages. These features make the mall a dynamic and engaging space for visitors of all ages.

Sustainability Initiatives

In recent years, Dizengoff Center has embraced sustainability as a core aspect of its design and operation. The center has implemented several green initiatives, such as:

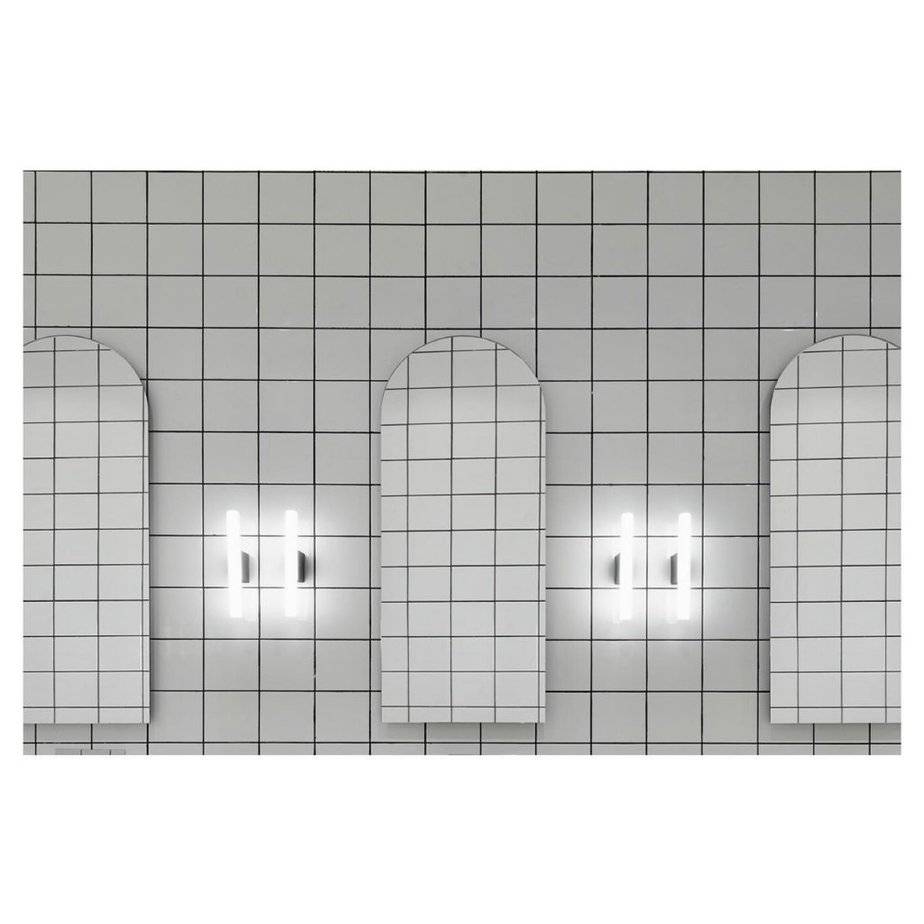

- Energy-Efficient Lighting: The use of LED lighting and automated systems helps reduce energy consumption.

- Recycling Programs: The center has established comprehensive recycling programs for waste management, encouraging both tenants and visitors to participate.

- Green Roofs: The installation of green roofs helps improve air quality, reduce the urban heat island effect, and provide insulation for the building.

Fun Facts

Historical Trivia

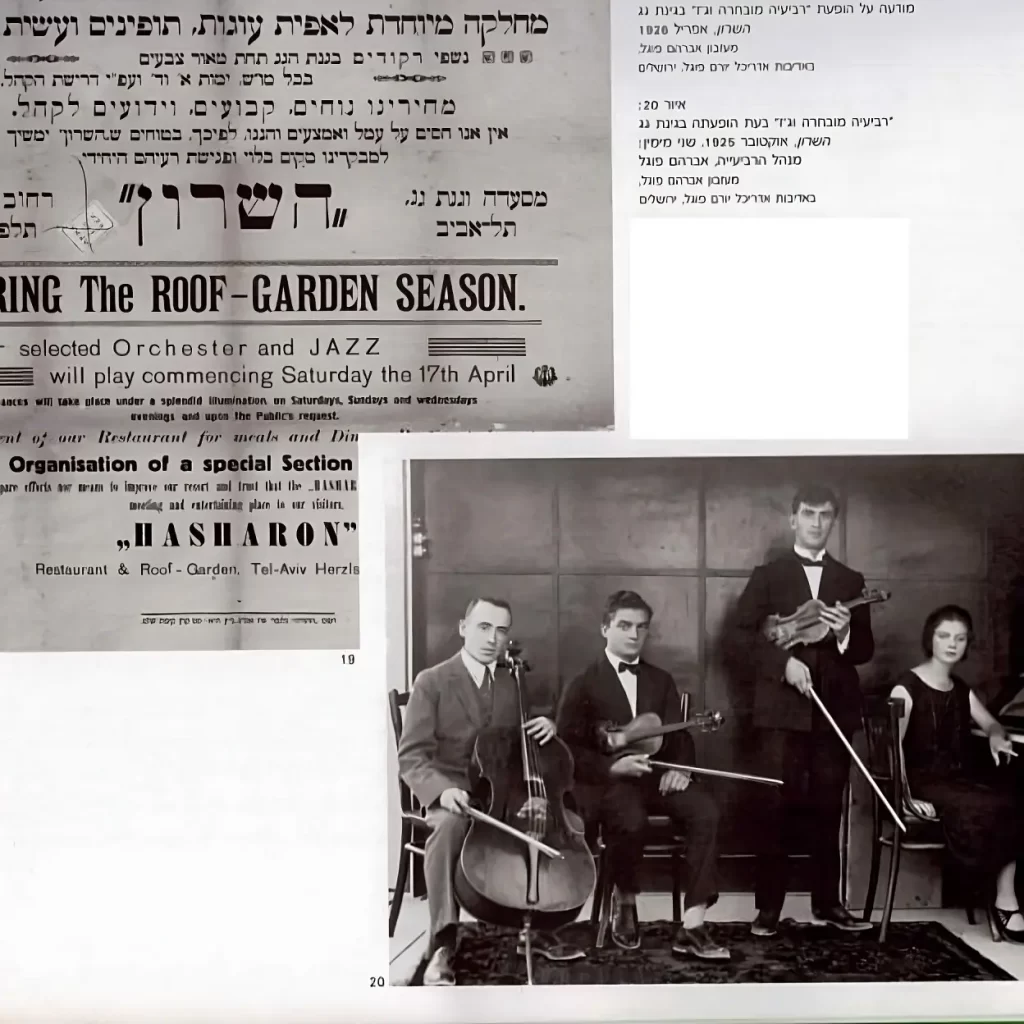

- Cinema Legacy: Dizengoff Center was home to one of Tel Aviv’s most iconic cinemas, the Dizengoff Cinema, which operated from 1977 until its closure in 1993. The cinema was famous for its midnight screenings and cult film festivals.

- Celebrity Visits: Over the years, Dizengoff Center has hosted numerous celebrities and public figures, including international movie stars and politicians, making it a hotspot for fans and media alike.

Cultural Impact

- Fashion Hub: Dizengoff Center is renowned for its vibrant fashion scene, hosting several fashion shows and events throughout the year. It is also home to many local designers’ boutiques, contributing to Tel Aviv’s reputation as a fashion capital.

- Food Market: The center’s food market is a popular attraction, offering a diverse array of culinary delights. From traditional Israeli cuisine to international flavors, the market reflects the city’s multiculturalism.

Architectural Curiosities

- Underground Passageways: Beneath the center lies a network of underground passageways that connect the different sections. These passageways were initially designed for logistical purposes but have since become part of the shopping experience.

- Rooftop Farm: In a unique twist, Dizengoff Center hosts a rooftop urban farm where various vegetables and herbs are grown. This initiative promotes urban agriculture and provides fresh produce for some of the center’s restaurants.

Impact on the City

Economic Contributions

Dizengoff Center has been a significant economic driver for Tel Aviv. It attracts millions of visitors annually, contributing to the city’s economy through retail sales, tourism, and employment. The center’s success has also encouraged investment in the surrounding areas, leading to broader economic development.

Social and Cultural Hub

Beyond its economic impact, Dizengoff Center serves as a social and cultural hub for Tel Aviv. It is a place where people from diverse backgrounds come together, fostering a sense of community and shared identity. The center’s events and activities, ranging from fashion shows to art exhibitions, enrich the city’s cultural landscape and provide a platform for creative expression.

Urban Renewal

The development of Dizengoff Center played a crucial role in the urban renewal of central Tel Aviv. Prior to its construction, the area was characterized by dilapidated buildings and a lack of commercial activity. The center’s establishment catalyzed a wave of revitalization, transforming the neighborhood into a vibrant and desirable part of the city.

Conclusion

Dizengoff Center is more than just a shopping mall; it is a testament to Tel Aviv’s evolution as a modern, dynamic city. Its history, architecture, urban planning, and design reflect the city’s innovative spirit and commitment to progress. Through its economic contributions, cultural initiatives, and social impact, Dizengoff Center has left an indelible mark on Tel Aviv, solidifying its status as an iconic urban landmark.

As Tel Aviv continues to grow and change, Dizengoff Center remains a constant, adapting to new trends and challenges while preserving its unique character. It stands as a symbol of the city’s resilience, creativity, and unyielding drive to be at the forefront of urban development and cultural innovation.

Check out “The Center 2023” by Kobi Farag, Morris Ben-Mayor. The movie The Center discovers the story and the history of Dizengoff Center, layer by layer, from the ground it was built on, to the top floor and the secrets this place withholds.

]]>Ben-Gurion, Slippers & Pigeons:

A New Statue Unveiled in Tel Aviv Old North

Take a stroll down Tel Aviv Old North on the iconic Ben-Gurion Boulevard, famed for its leafy promenade and historic architecture, and you’ll now encounter a new sight: a life-sized bronze sculpture of David Ben-Gurion, Israel’s first Prime Minister, and his wife Paula. But forget grandiose poses and heroic gestures – this statue captures them in a disarmingly ordinary moment.

Beyond the bustling streets and vibrant energy of Tel Aviv’s iconic Ben-Gurion Boulevard lies a new sight: a life-sized bronze sculpture capturing a heartwarming glimpse into the lives of Israel’s first Prime Minister, David Ben-Gurion, and his wife Paula. But forget grand poses and heroic gestures. This statue, crafted by artist Shira Zelwer, transcends expectations by portraying them in a disarmingly ordinary moment.

Forget what you know about statues of national heroes. Picture Ben-Gurion, hands in pockets, casually gazing ahead, while Paula, slippers peeking out, stands next to him, looking towards their former home across the street. A scattering of bronze pigeons completes the scene, evoking the everyday bustle of the city.

Why the slippers and pigeons? Artist Shira Zelwer didn’t want the usual, monumental portrayal. Instead, she aimed to reveal the human side of this iconic couple. Imagine them as any Tel Aviv resident enjoying a moment outside, perhaps discussing the day’s news or simply taking in the city air.

This unique perspective adds a fascinating layer to exploring Tel Aviv, particularly the “Old North” neighborhood where Ben-Gurion Boulevard lies. While this area is known for its charming historic buildings and vibrant real estate scene, the statue reminds us that history wasn’t made solely in grand spaces, but also in everyday moments like these.

The statue serves as a reminder that even figures of great historical significance were, in their private lives, simply ordinary people navigating daily moments. It’s a poignant counterpoint to the grand narratives of history, reminding us that greatness often resides in the quiet moments of connection and shared humanity.

Moreover, the Ben-Gurion statue adds another layer to the rich tapestry of Tel Aviv’s Old North neighborhood. This area, known for its charming historic buildings and vibrant real estate scene, now also offers a window into the personal history of one of Israel’s most iconic figures. So, take a stroll down Ben-Gurion Boulevard, discover this captivating sculpture, and perhaps, you’ll be inspired to see both the history and the humanity that resides at the heart of this dynamic city.

Zelwer, a rising star in the Israeli art scene, deliberately chose to forgo the monumental approach often associated with statues of national figures. Instead, she sought to reveal the human side of the Ben-Gurions. Imagine them as any Tel Aviv couple enjoying a walk, perhaps discussing the day’s news or simply taking in the city air. This relatable portrayal invites us to see Ben-Gurion not just as a statesman, but as a husband, a neighbour, and a fellow resident of Tel Aviv.

The statue serves as a reminder that even figures of great historical significance were, in their private lives, simply ordinary people navigating daily moments. It’s a poignant counterpoint to the grand narratives of history, reminding us that greatness often resides in the quiet moments of connection and shared humanity.

Intrigued? Want to see it for yourself? Ben-Gurion Boulevard is a must-visit on any Tel Aviv trip, offering a beautiful green escape within the bustling city. And now, thanks to this new sculpture, you can experience a slice of Israeli history in a refreshingly relatable way.

]]>Bauhaus Blending Sunshine: Why this Architectural Style Thrives in Hot Climates (Especially Tel Aviv!)

When you think of Tel Aviv, images of luxury real estate bathed in warm sunlight likely come to mind. But have you ever wondered why the city’s architectural style seems so perfectly suited to its hot climate? Look no further than Bauhaus, the iconic movement that left its indelible mark on Tel Aviv’s skyline and continues to influence Tel Aviv real estate to this day.

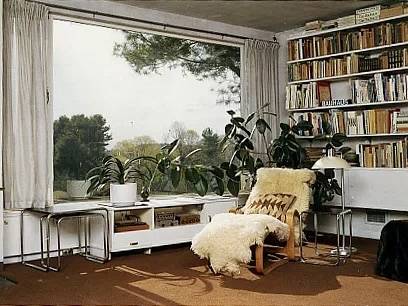

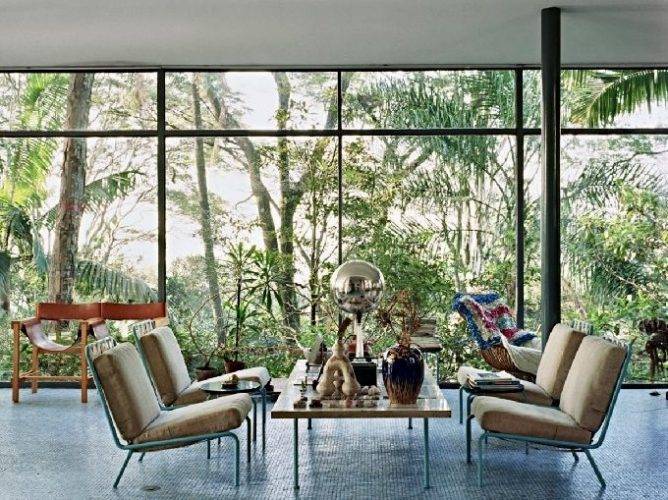

Bauhaus Basics: Born in Germany in the early 20th century, Bauhaus emphasized functionality, clean lines, and a seamless integration of indoor and outdoor spaces. This philosophy proved a perfect fit for Tel Aviv’s Mediterranean climate, where residents crave light, air, and connection to nature.

Key Features for Hot Climates: Here’s how specific Bauhaus elements contribute to thermal comfort and livability in hot regions:

Tel Aviv’s Bauhaus Boom: In the 1930s, Tel Aviv witnessed a flourishing of Bauhaus architecture. Thousands of white, boxy buildings with balconies and expansive windows sprang up, creating a unique urban landscape. This “White City” earned Tel Aviv its UNESCO World Heritage Site status and continues to attract admirers worldwide.

Modern Relevance: The appeal of Bauhaus extends beyond aesthetics. In today’s Tel Aviv real estate market, buyers recognize the benefits of these sustainable and adaptable designs. Luxury real estate featuring Bauhaus elements often commands premium prices due to their inherent functionality, timeless style, and connection to the city’s heritage.

Considering Tel Aviv Luxury Real Estate?

If you’re drawn to the charm and practicality of Bauhaus architecture, Tel Aviv offers a wealth of luxury real estate options featuring this iconic style. From historic apartments to contemporary interpretations, you’re sure to find a space that perfectly blends modern comfort with timeless design.

Beyond Tel Aviv: The influence of Bauhaus can be seen in hot climates around the globe, from California to Israel’s desert city of Mitzpe Ramon. Its principles of functionality, light, and connection to nature remain relevant, proving that good design transcends borders and climates.

Bauhaus Beyond Borders: How a German Design Movement Traveled the World

The Bauhaus, a revolutionary architecture and design movement born in Germany in the early 20th century, wasn’t confined by national borders. Its ideals of functionality, clean lines, and the integration of indoor and outdoor spaces resonated with architects worldwide, adapting and transforming in diverse cultural contexts. Let’s embark on a journey to explore how Bauhaus manifested in five distinct nations: Venezuela, Mexico, Italy, India, and Iran.

Venezuela: Caracas and the Tropical Reinterpretation: In the 1940s, Caracas embraced Bauhaus principles to modernize its rapidly growing cityscape. Architects like Carlos Raúl Villanueva incorporated open floor plans, expansive windows, and geometric forms into iconic structures like the Central University of Venezuela, a UNESCO World Heritage Site known for its airy, light-filled spaces perfectly suited to the tropical climate.

Mexico: Reimagining Tradition with Modernity: Mexico’s encounter with Bauhaus resulted in a unique blend of European modernism and local vernacular architecture. Architects like Luis Barragán seamlessly integrated open layouts, exposed concrete, and traditional materials like volcanic rock into their designs, creating masterpieces like the San Cristobal House, where indoor and outdoor spaces blur, reflecting Mexico’s deep connection to nature.

Italy: A Dialogue Between Past and Present: In Italy, the Bauhaus influence encountered a rich architectural heritage, leading to a more nuanced interpretation. Architects like Gio Ponti adopted streamlined forms and functionality while incorporating Italian design traditions like vibrant colors and handcrafted details. This approach can be seen in the iconic Pirelli Tower in Milan, where a modern glass facade complements a historical context.

India: Redefining Modernity in a Postcolonial Landscape: In India, Bauhaus principles arrived during a period of national awakening and cultural rediscovery. Architects like Charles Correa adapted the movement’s emphasis on light and ventilation to the Indian climate, while incorporating traditional elements like courtyards and water features. This can be seen in the Gandhi Institute of Ahmedabad, where modern design coexists with vernacular influences.

Iran: A Fusion of East and West: In Iran, Bauhaus encountered a vibrant artistic heritage rich in geometric patterns and intricate details. Architects like Houshang Seyhoun integrated these elements into their modern designs, creating a unique fusion of Eastern and Western aesthetics. This is evident in the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art, where geometric forms and traditional tilework coexist in a harmonious dialogue.

In conclusion, the Bauhaus story extends far beyond Germany. By examining its diverse manifestations in Venezuela, Mexico, Italy, India, and Iran, we gain a deeper understanding of how a design movement can adapt and evolve in different cultural contexts. Each nation reinterpreted the Bauhaus principles to create unique architectural expressions that reflected their local identities and climatic needs. This global journey demonstrates the enduring relevance of Bauhaus ideals and their ability to inspire architects and designers worldwide.

Note: This essay provides a starting point for further exploration. Each nation’s Bauhaus story deserves a deeper dive into specific architects, projects, and the broader cultural context. Feel free to expand on specific examples or delve into individual countries for a more detailed analysis.

Considering Tel Aviv Luxury Real Estate? If you’re drawn to the charm and practicality of Bauhaus architecture, Tel Aviv offers a wealth of luxury real estate options featuring this iconic style. From historic apartments to contemporary interpretations, you’re sure to find a space that perfectly blends modern comfort with timeless design.

Remember, Tel Aviv real estate is a dynamic market. For expert guidance in navigating your options and finding the perfect Bauhaus-inspired dream home, get in touch with one of our team.

]]>Architect, Engineer, Entrepreneur, Builder

Engel 7

The building was designed by the architect Avraham Kaviri. Kaviri was born in 1903 in Ukraine and immigrated to Israel in 1922. During the evenings, he studied building engineering at the Montefiore Technical Institute, while during the day he worked as a construction laborer to support himself.

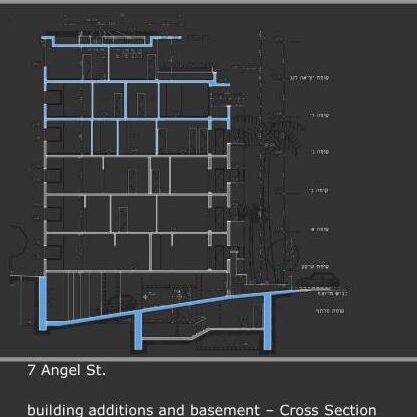

In 1926, he was involved in the construction of the Naharayim power station, and a year later, he traveled to France to study civil engineering at the University of Caen. Among the buildings he erected are: Engel 7, Idelson 13, Shmaryahu Levin 11, Shlomo Hamelech 70, Bar Kochba 50, and Shlomo Hamelech 11 and 38. The plot, covering an area of 597 square meters, was purchased by Meir Arison in February 1935 for the price of 1,100 Palestinian pounds.

The building plans were submitted for approval in May of that year; the construction permit was received less than a month later, and six months afterward, on December 9, 1935, the construction was completed.

The first owner, Meir Arison, was a dominant figure in the economy of the Yishuv. He was born in Zichron Yaakov in 1894 to Moshe and Sarah, early settlers and founders of the colony. Meir studied in the colony and later traveled to Istanbul for studies at a commerce school.

In 1914, he was drafted into the Turkish army and served as an officer. His position enabled him to assist Meir Dizengoff in helping the refugees of Tel Aviv and Jaffa and easing the siege in his hometown after the NILI underground was discovered. Helping Dizengoff paid off, as after the war, the city’s head invited him to manage an export-import office, and over time, he also became a partner in his firm.

Thanks to his talents and impressive language skills, he greatly contributed to private businesses, in particular, and the Hebrew economy in general, even receiving honors and excellence awards for developing foreign relations with Romania, France, and Belgium. In 1946, after his death, the property on Engel Street passed to his heirs.

In 1949, the building was connected to the municipal sewage system, as until then, absorption pits had been used. In the 1950s, three discharged soldiers opened an automatic laundry service in the basement of the building, and in addition, a workshop for producing kippahs operated in the basement.

From a historical value standpoint, the building reflects the great wave of immigration in the 1930s, which required the construction of 3-4 story buildings, replacing smaller houses. The building, like many around it, was built in the International Style prevalent in Tel Aviv during those years—a style that expressed social and cultural perceptions, primarily functionality and catering to the needs of a city undergoing development and growth.

The building has undergone almost no changes over the years until its preservation by “White City Buildings” and has maintained its unique features: it was built in the shape of an ‘H’ (towards its rear facade), with an inner green courtyard for the private use of its residents; its facade is divided into two sections, with only the ground floor differing, and the entrance breaking the symmetry.

Nevertheless, the facade has pleasant proportions; the public interior spaces, such as the entrance and staircase room, were carefully designed, likely by Kaviri, with attention to detail: from the unique railing, through the entrance door, to the lamps—all to preserve the overall harmony that characterized the house.

The building employed sliding windows, which were not typical in the 1930s, and was built using “modern” methods that included the use of angled concrete, select bricks, columns, and washed plaster (Washputz), methods that characterized the International Style.

Avraham Kaviri, the architect, was born in 1903 in Ukraine and immigrated to Israel in 1922. Throughout his career, Kaviri made significant contributions to the development of Israeli architecture. His background in building engineering, which he acquired at the Montefiore Technical Institute, combined with his practical experience working as a construction laborer, provided him with a solid foundation for his architectural practice. Kaviri’s architectural style was influenced by the International Style, which was prevalent in Tel Aviv during the 1930s. This style focused on functionality, simplicity, and the use of modern materials and techniques.

It was characterized by clean lines, minimal ornamentation, and a preference for open spaces and large windows, which allowed for the natural flow of light and air. In addition to the International Style, Kaviri was likely influenced by the Bauhaus school, which promoted the idea that form should follow function. This philosophy placed emphasis on designing buildings that met the practical needs of their inhabitants, while also achieving a high level of aesthetic quality. Kaviri’s designs often featured elements such as flat roofs, white or lightly colored facades, and an overall streamlined appearance, which were typical of Bauhaus architecture.

Another significant influence on Kaviri’s work was the local architectural traditions and building techniques of Israel. He often incorporated elements of vernacular architecture, such as the use of local materials, climate-responsive design, and the integration of green spaces, like courtyards and gardens.

This allowed Kaviri’s buildings to be both environmentally sustainable and well-suited to the needs of their inhabitants. Kaviri’s architectural designs were marked by careful attention to detail and an emphasis on harmony and balance.

He skillfully combined elements of the International Style with local building traditions, creating buildings that were both functional and aesthetically pleasing. His work stands as a testament to the architectural innovation and creativity that characterized the early years of the Zionist movement and the development of modern Israeli architecture.

During the same period as Avraham Kaviri, several other prominent architects were also shaping the architectural landscape of Tel Aviv.

These architects played a significant role in developing the city’s distinct architectural identity, which was characterized by a fusion of International Style, Bauhaus principles, and local traditions.

Yehuda Magidovitch: Often considered the first city architect of Tel Aviv, Yehuda Magidovitch designed many prominent public and private buildings throughout the 1920s and 1930s.

His work includes the Great Synagogue on Allenby Street, the Esther Cinema, and numerous residential buildings. Magidovitch’s style combined elements of Art Deco, Eclecticism, and later, the International Style.

Dov Karmi: A leading architect in Tel Aviv during the 1930s and 1940s, Dov Karmi was known for his functional and modernist approach. He designed several iconic buildings, including the historic “Migdal HaShalom” (Shalom Tower) and the Heichal Hatarbut (Mann Auditorium). Karmi’s work was influenced by the International Style, Bauhaus principles, and Brutalism.

Arieh Sharon: A prominent Bauhaus-trained architect, Arieh Sharon was responsible for designing numerous residential and public buildings in Tel Aviv during the 1930s and 1940s. His work includes the Workers’ Bank Building, the Histadrut Labor Federation Building, and the Hadassah Hospital in Jerusalem. Sharon’s designs were characterized by functionalism, clean lines, and a focus on the needs of the building’s inhabitants.

Shmuel Barkai: Active during the 1930s and 1940s, Shmuel Barkai designed several notable residential buildings in Tel Aviv. His work was characterized by a unique combination of the International Style and local architectural traditions. Barkai’s designs often featured flat roofs, horizontal windows, and an emphasis on natural light and ventilation.

Ze’ev Rechter: Another influential architect of the period, Ze’ev Rechter designed a range of public and residential buildings in Tel Aviv. His work includes the iconic Frug House and the Central Bus Station. Rechter’s architectural style combined the International Style with local materials and techniques, creating a distinctive blend of modernism and tradition.

These architects, along with Avraham Kaviri, played a significant role in shaping the architectural landscape of Tel Aviv during its formative years. Their innovative designs and the fusion of various architectural styles contributed to the development of the city’s unique architectural identity, which is still evident in its many preserved and restored buildings today.

Beit Shik

90 HaYarkon Street, Tel Aviv-Yafo – Beit Shik Project Essence: Local Preservation of a Historic Structure Status: Completed Program: Residential and Commercial Start Year: 2002 Completion Year: 2010 Initiator: Private Project Description:

The project was based on the preparation of a localized TABA (Urban Building Plan) that annulled an expropriation previously made for the purpose of expanding the road, thus allowing for the preservation of the building.

The building was in an extremely dilapidated physical condition, primarily due to its proximity to the sea and chronic lack of maintenance.

The ground floor café was restored to its former state, while the two floors above were adapted for residential use. The addition of two floors atop the preserved building enabled the economically viable preservation process.

Background: Beit Shik, situated opposite the sea at the corner of Bograshov and HaYarkon streets, was designed by architect Avraham Kaviri in the International Style for the Shik family.

The residential building was constructed between 1934 and 1935. In 1937, the ground floor was converted into a café-restaurant. The building’s location along the first line of the seafront, above London Garden, grants it a secondary importance as part of Tel Aviv’s cityscape, as viewed from the sea and the beach.

Perlman House

In March 1939, a letter was sent on her behalf in which she pleaded with the officials to allow her to open shops on the facade facing Bar Kochba Street. All to no avail. On the other hand, approval was granted in 1944 to construct a single-room apartment on the roof of the building.

In the meantime, part of the ground floor was rented to ‘Katz Gallery,’ which exhibited works by Tel Aviv artists. Perlman House – 79 Dizengoff Street, corner of 50 Bar Kochba Street. In 1930, Yaakov Hershkovitz, who owned a shed on the corner plot at the intersection of Dizengoff and Bar Kochba streets, received approval to construct a two-room residential building, with a kitchen and balcony, along with a toilet. After two or three years, the building was sold to contractor Abraham Kabiri and his two partners, who added the two upper floors in 1934. Construction was delayed due to recurring disputes with the neighbor at 48 Bar Kochba Street, who claimed that the partners were encroaching on his property.

The matter of opening shops on the ground floor, as the partners wished, also sparked conflicts with neighbors and the technical department of the municipality. Within a year, the building was sold to Mrs. Mina Perlman. It seems that the savvy sellers did not inform her of the disputes related to opening the shops.

In October 1935, the building engineer she hired wrote a letter to the technical department on her behalf: “…This house has passed to the new owners who knew nothing of the existing situation and accepted the building in confidence that they were allowed to open a shop on the first floor, so why should they now be punished for their lack of knowledge, as if ‘the fathers ate sour grapes and the children’s teeth were set on edge?'”

The small neighborhood where the house is located was called ‘Trumpeldor Neighborhood.’ It was a neighborhood of shacks, situated between the larger and more well-known ‘Nordia’ and the Select Brick Manufacturing Factory, which was adjacent to ‘Tel Nordau’ neighborhood.

Mrs. Perlman’s request to lease a space to a man who wanted to open a bicycle repair shop was rejected. The saga continued for several years. A breakthrough regarding approved commercial spaces occurred during the War of Independence. At that time, demobilized soldiers or war wounded were allowed to open businesses, bending the rules, even in places previously designated for residential use only.

Thus, two discharged soldiers opened a laundry on the ground floor of the building. During the 1950s, ‘Gershon,’ a bicycle repair and sales shop, was operating here, as well as the ‘Yitzhak’ taxi station. The bicycle shop changed owners and remained in business until the 1980s. The taxi station was replaced by a clothing store, and since then, food and fashion businesses have dominated the area.”

Dreaming of Amsterdam

Tel Aviv cycle paths

Tel Aviv cycle paths

Tel Aviv cycle paths

Tel Aviv cycle paths

Tel Aviv cycle paths

Tel Aviv is no different than all other metropolitan cities when it comes to traffic congestion. Some would say it’s worse. If you’ve visited recently you will have noticed that the city is one big building site. The works of the metro are well underway, office towers and residential buildings are propping up at an astonishing pace. All that said, moving around in the city has become challenging and since we are blessed with eternal sunshine, biking has become the preferred means of transportation for a great number of Tel Avivians.

Unsurprisingly, the mayor, Ron Huldai, was re-elected, on the back of a bold Tel Aviv cycle paths agenda. Promising a substantial increase in lanes all round and through the city. That’s great news for most and a nightmare for others. The city is undergoing a major shift and priority is given to the more ecologically sensitive solutions. With the Tel Aviv cycle paths come a flurry of urban improvements such as parks and pedestrianised neighborhoods. A great example is the Park Hamesila in Neve Tzedek. A gorgeous promenade on the Ottoman era former rail tracks. Once a no man’s land where you’d be foolhardy to wander at night is now a beautifully landscaped lane, (no too dissimilar to New York’s High Line), where families gather to picnic and kids run free.

Tel Aviv-Yafo’s flat topography and comfortable climate make for a perfect environment to bicycle in. With the help of a bicycle you can get around the city through the fastest routes, without traffic or parking tickets. The Tel Aviv-Yafo Municipality has made it its top priority to encourage bicycle and scooter riding across the city. Cycling reduces parking issues, decreases traffic and gas expenses. It is cheaper, better for the environment and for the cyclists themselves as it improves fitness and increases bodily adrenaline levels. According to the recently passed ambitious plan , there will 283 kilometers additional cycle paths in Tel Aviv. The project is part of a national master plan aimed at raising the proportion of journeys made by bicycle to 10%.

By 2025, Tel Aviv cycle paths will be increased by 283 kilometers

Planned Tel Aviv Cycle Paths

Existing Tel Aviv Cycle Paths

All is not rosy though…

While were all patiently for the city to turn into a mediterranean bucolic version of Amsterdam, the widespread use of the infamous electric scooters has made leisurely strolling a nerve racking and life threatening activity. The Rothschild boulevard and the boardwalk both boast comfortably wide cycle paths. The small and narrow side streets, however have turned into war zones, where bikes, strollers, scooters, parked cars, pedestrians and cats struggle for their piece of the sidewalks… Like everything, the Tel Aviv municipality has a history of “crossing the bridge when they get there”, but eventually, whole neighborhoods have already drastically improved, especially in Florentine or Shapira.

The project is part of a national master plan aimed at raising the proportion of journeys made by bicycle to 10%.

On Monday, the Tel Aviv District Planning and Building Committee, headed by Eran Nitzan, will discuss the master plan for the Tel Aviv Cycle Paths. The plan, details of which have reached “Globes”, calls for the paving of 758 kilometers of cycling paths, and is one of several plans being promoted as part of a general national plan. The test, however, will be in the execution of the projects in the urban space at the expense of lanes for private cars and parking spots, something in which the Ministry of Transport has not excelled up to now.

The plan is meant to achieve the goals set for the breakdown of the use of different means of transport, according to which 12% of journeys in the Tel Aviv district should be by bicycle, which compares with 3% today. For Tel Aviv itself, the target is 20%, which compares with 7% today. For other local authorities in the district – Azor, Ramat Gan, Ramat Hasharon, Or Yehuda, Holon, Bat Yam, Herzliya, Kiryat Ono, Givatayim, Kfar Shmaryahu, and Bnei Brak – the targets are substantially higher than the current rate of use of bicycles. The planned 758 kilometers of cycling paths are in addition to the existing 251 kilometers, and mostly in Tel Aviv.

Tel Aviv Cycle Paths, Ramat Gan 69 kilometers, Herzliya 90 kilometers, Holon 75 kilometers, with the rest spread over the remaining local authorities. The paths will cross 146 bridges, some of them already in existence and some approved for construction, and the plan proposes adding another nineteen bridges for bicycles. The plan is based on surveys of existing traffic and forecasts of future demand.

Priority will be given to streets in which bicycle traffic is above the regional average, streets that will complement an efficient network of paths without dead ends and that connect to the Ofnidan network of long-range bicycle paths, and that have advanced planning status. The network’s coverage is meant to bring buildings within 250 meters of cycling infrastructure. Coverage on that basis will rise from 42% today to nearly 90%.

The existing rate of bicycle use varies widely between one local authority and another, with Tel Aviv in the lead by a long way. An international comparison presented in the plan shows Tel Aviv towards the top of cities promoting cycling infrastructure, but the rest of the Dan region lags far behind.

The plan was drawn up by the Ministry of Transport, the Planning Administration, and consultants Planet and Eshed, and is part of a more comprehensive national plan that sets out how many kilometers of cycle paths are required in the built-up areas in all of Israel. The budget estimate for the whole network is NIS 8 billion, divided into five-year portions, NIS 2 billion for each five-year period. This substantially raises the investment per capita in cycling infrastructure in Israel, and, unlike various other master plans, this one rests on a budget that has already been partly passed. Cycling networks for the other metropolitan areas – Haifa, Jerusalem, and Beersheva – will be derived from the national master plan, and a network will be completed to cover the central district.

The goal: Ten times more journeys by bicycle

The working assumption behind the national master plan is that it is possible to reach a proportion of 10% of journeys being made by bicycle, compared with just 1% today. The general rate at which bicycle paths are being paved in Israel is low, at just 32 kilometers annually, whereas in Tel Aviv cycle paths are being paved fairly rapidly; half the national total for 2020 was in Tel Aviv. To reach the national target of over 3,700 kilometers of cycle paths will cost nearly NIS 8 billion over twenty years. The budget for the next five years works out at about NIS 39 annually per resident, up from NIS 10 previously. In the leading cycling countries the budgets are higher, even though they already have well-developed cycle path networks. The UK, for example, invests about NIS 50 annually per resident in cycling infrastructure, Germany invests NIS 32-70, and the Netherlands NIS 138.

The plan represents a considerable advance in both planning and budgeting, but the test will be execution, in which the Ministry of Transport is weak, as demonstrated by many transport initiatives.

Even agreements with the local authorities are no guarantee of performance. In 2016, for example, the Ministry of Transport signed a series of agreements with local authorities on paving preferential traffic lanes for buses. Many of the authorities, however, caused difficulties at the execution stage, in some the mayor changed and policy along with that, and some simply started to wriggle out of the agreements. Another initiative is Ofnidan, which the Ministry of Transport undertook, unrealistically, to complete in 2021. In fact, the project is still incomplete, after being frozen during Miri Regev’s period as minister of transport.

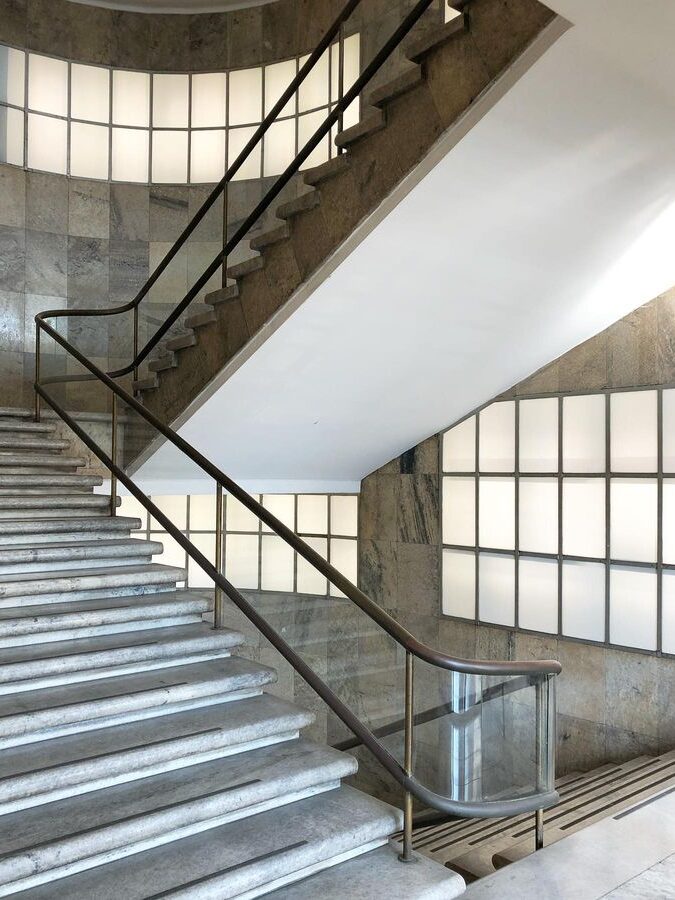

Bauhaus Hidden Treasures: Tel Aviv’s Most Beautiful Stairwells

Tel Aviv Bauhaus Staircases

Tel Aviv Bauhaus Staircases

Tel Aviv Bauhaus Staircases

Stairwells are the core of any structure and the students at the Bauhaus School in Dessau were taught that all the elements of building should reflect the founding principles of the institutions. Those principles were applied to everything, whether a chair, a tea pot or a building. Great care was taken when designing the staircases as they constitute a natural buffer, or a transition rather between the outside world and the homes.

Tel Aviv Bauhaus Staircases

Tel Aviv Bauhaus Staircases

«No border between art and craft.»

The carpentry of the balustrade, the ironwork of the stair railing, the intricate elliptical walls were all opportunities to showcase the craftsmanship of the people involved in the building. In a pamphlet for an April 1919 exhibition, Gropius stated that his goal was «to create a new guild of craftsmen, without the class distinctions which raise an arrogant barrier between craftsman and artist». It is said in the manifesto, that «architects, sculptors, painters, we must all turn to the crafts!».

«Form follows function».

Tel Aviv Bauhaus Staircases

According to this idea, simple but elegant geometric shapes were designed based on the intended function or purpose of a building or an object. The staircase is probably the one feature with simplest yet vital function. That needn’t have to be boring and the Bauhaus students added new dimensions to the staircases primary role. Some may even say they brought in a spiritual element to their designs in order to elevate the visitor. Spirituality, by the way, was an integral part of the school and permeated through all the designs.

Vassily Kandinsky, for example, who joined the Bauhaus in the summer of 1922, was committed to transcendentalist theories espoused by Austrian philosopher Rudolf Steiner and proponents of the anthroposophist movement. Through non figurative compositions Kandinsky attempted to formulate objective laws for the expression of subjective experiences, and he saw the school as a vehicle for the development of his spiritually.

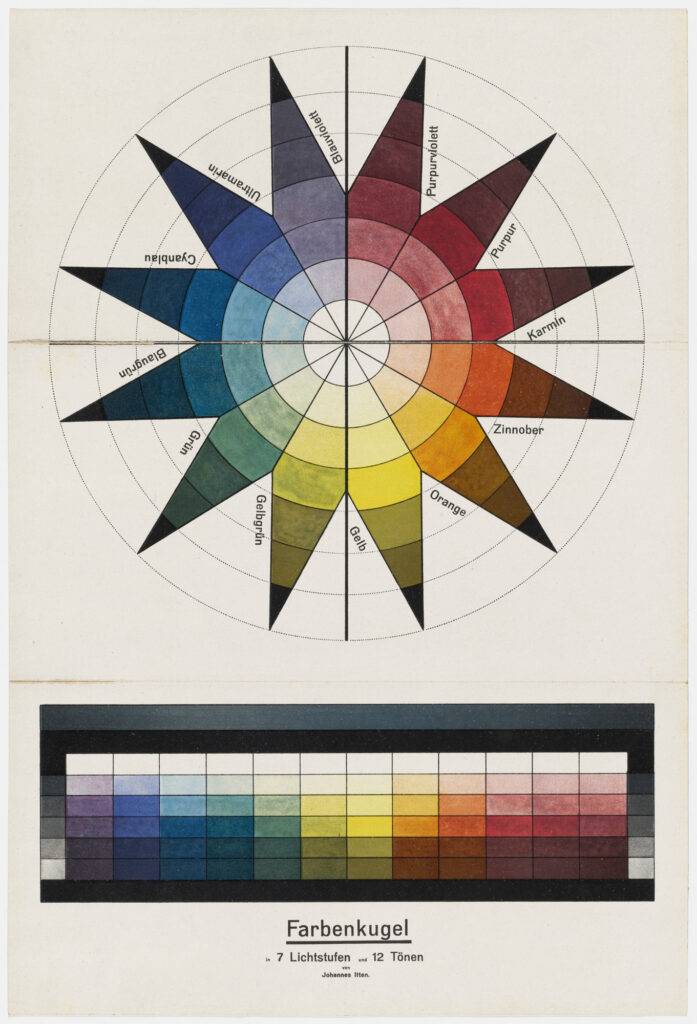

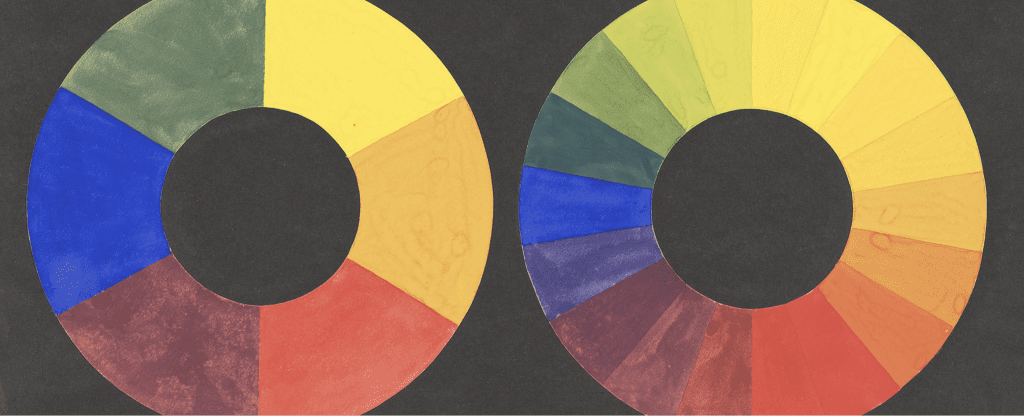

«Color Theory»

Tel Aviv Bauhaus Architecture

The Preliminary Course at the Bauhaus introduced all first-year students to what were considered the fundamental principles of color, form, and material. Through lectures, demonstrations, and exercises, they were to develop familiarity with the “basic elements” of art and design, including points, lines, and planes; triangles, squares, and circles; and the primary colors. Teachers aimed to promote a shared foundation of aesthetic knowledge among the student body through these investigations.

The Bauhaus masters—each armed with his or her particular theories and interests—spearheaded the first-year studies. Johannes Itten initiated the Preliminary Course in the fall of 1920; László Moholy-Nagy and Josef Albers took over beginning in 1923. Albers led it alone after 1928.

These courses were supplemented by specialized theoretical seminars taught by key Bauhaus faculty, including Gertrud Grunow, Vassily Kandinsky, Paul Klee, Oskar Schlemmer, and Joost Schmidt. The masters agreed that a firm grounding in the principles of form and color was crucial to the development of a new generation of artists. These fundamentals remained at the core of Bauhaus education until the closure of the school in 1933.

Stairwells are the core of any structure and the students at the Bauhaus School in Dessau were taught that all the elements of building should reflect the founding principles of the institutions. Those principles were applied to everything, whether a chair, a tea pot or a building. Great care was taken when designing the staircases as they constitute a natural buffer, or a transition rather between the outside world and the homes.

Tel Aviv is full of those gems. Next time you stroll around Rothschild Boulevard in Lev Ha’Ir, just take a quick peek into some the staircases of Bauhaus buildings. The more run down, the better as they are more likely to have retained some of the original features.

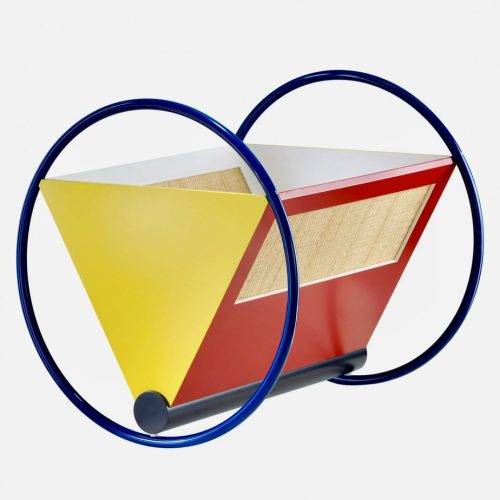

Bauhaus Design Extends Beyond Architecture into a Phenomenal Force

Bauhaus design whose father Walter Gropius thought of design scientifically, with functionality at its core became the single most important design movement. Its influence reached beyond the architecture in Germany and Tel Aviv, much in the same way that Cubism revolutionized art. And of course it started with the architecture, the enveloppe.

The principles that underpinned the elaboration of a building or house made their way inside and the Bauhaus students were expected to design any space in wholistic manner, from the structure all the way to the door handles, the colors and the art. Gropius did see a distinction between the artisan and the artist. The same way the artisan would craft a chair with a clear functional goal, emphasized the function of the object, the simplicity of forms, and a lack of extraneous ornamentation or decoration.

Art was taught at the Bauhaus school with the objective to let students penetrate into the essence of things and understand abstraction; «the Basics of artistic design», which are, in fact, the theory of the design and the famous course on the “Theory of Color”. In this course, artists like Kandinsky taught the theory of color from the history of development of various color systems to modern psychology of perception of color.

The premise of the theory, which was then later developed, lied on the identification and distinction of seven color categories: hue, light-dark, cold-warm, complementary, analogous, saturation, and extension.

Wassily Kandinsky, who pioneered abstract art in the early 20th century, had a rare trait called synaesthesia, which blurs the senses and allowed the Russian painter to associate colours with certain sounds and moods. Red, he heard as a violin; yellow, as a trumpet; and blue, the sound of a heavenly organ.

Furniture design was approached with the same scientific method as art. Teachers at the Bauhaus introduced the distinction between “matter” and “material”. The study of matter consisted of the comparison of different materials relative to each other, whereas the study of materials pertained to the properties of a single material. This approach allowed for the discovery and use of new materials in furniture design, to improve performance, durability and cost.

Can functional Bauhaus design be beautiful?

In a lecture given in 1932, the transcription of which appeared in the review Werk (Breuer, 1932), Marcel Breuer attempted to distinguish between modern and fashionable. For the Bauhaus architect and furniture designer, one of the fathers of modernism, the drive for innovation– of the object, of the habitat, of life – drives, under the pressure of logic and of passion, modernism.

Fashionable objects, on the other hand, would be the product of a mood, of a “healthy boredom” which arises from our need for entertainment and variety. To confuse the two would be harmful: the modern movement runs the risk of running out of steam, explains the author, because it will have been defended “with a narrowness of mind which, in order to appear modern at all costs, has succumbed to the allure of fashion “.

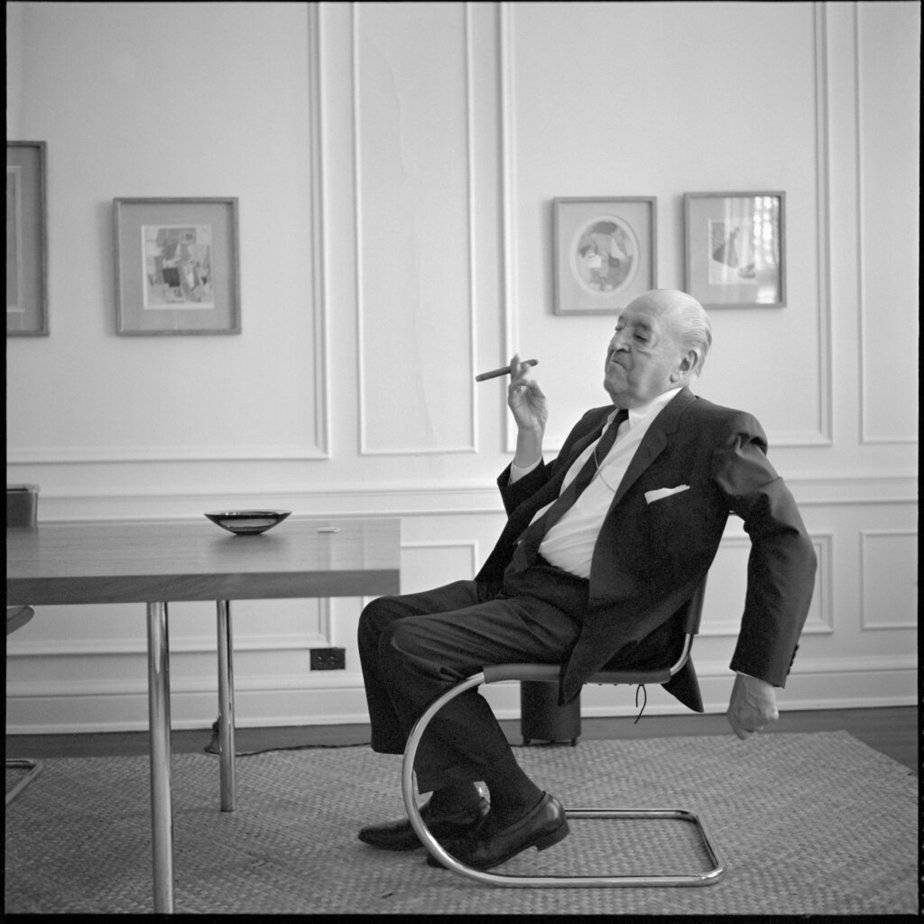

Ludwig Mies van der Rohe

Not all architects shared Breuer’s opinion. Charlotte Perriand, who worked with Le Corbusier, understood that the a home decor should spark joy and happiness. She then coined the expression “fonctionalisme excessif” whereby the quest for the ultimate came at the expense of esthetics. Charlotte Perriand would never have submitted to this excessive functionalism. For her, living should be a pleasure, a celebration renewed every day, and for that it was necessary to have a friendly space.

The male dominated movement became synonymous with austerity. The ideal living space would count the bear minimum. It did however change design for ever.

Our Bauhaus Inspiration Board