Bauhaus Design Extends Beyond Architecture into a Phenomenal Force

Bauhaus design whose father Walter Gropius thought of design scientifically, with functionality at its core became the single most important design movement. Its influence reached beyond the architecture in Germany and Tel Aviv, much in the same way that Cubism revolutionized art. And of course it started with the architecture, the enveloppe.

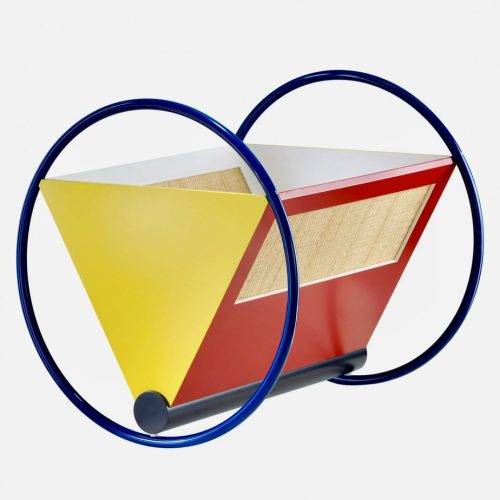

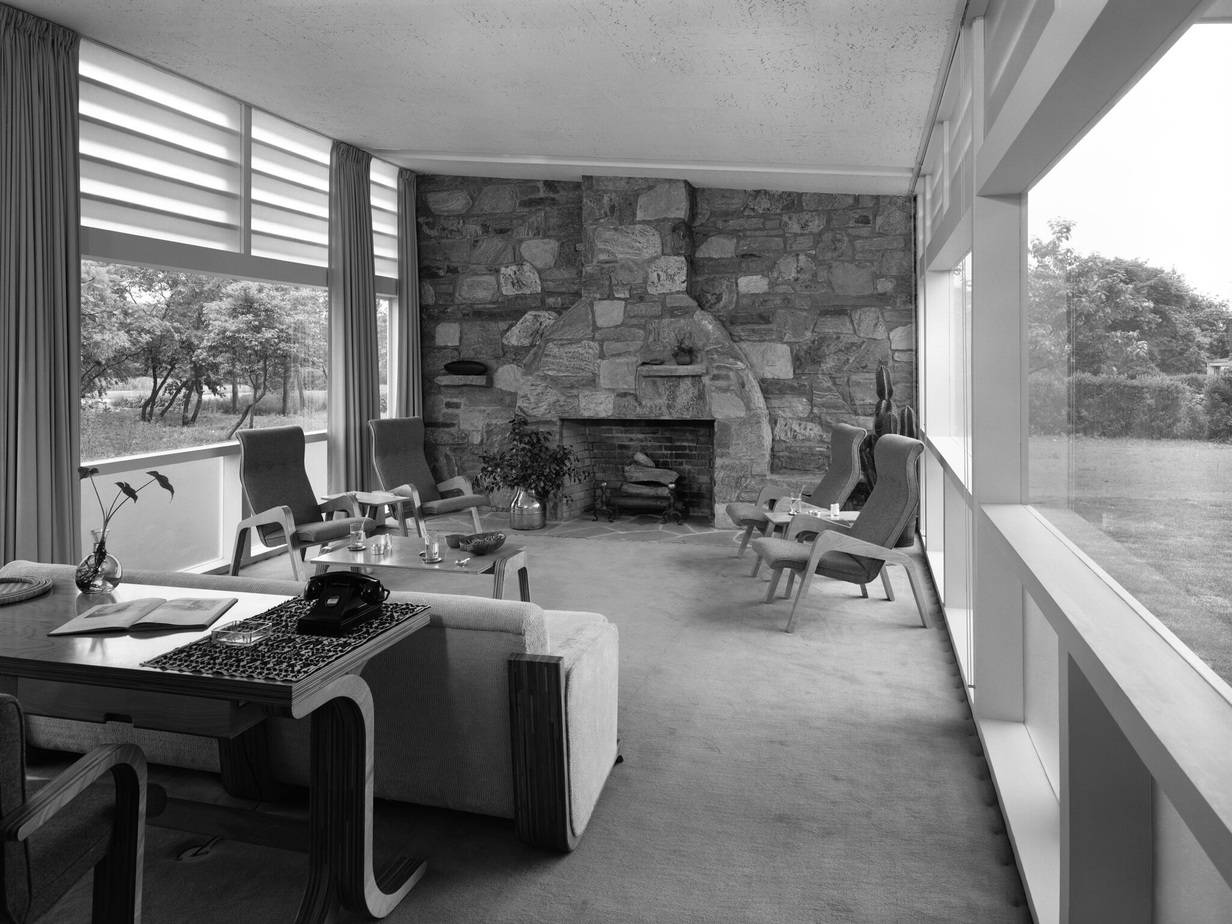

The principles that underpinned the elaboration of a building or house made their way inside and the Bauhaus students were expected to design any space in wholistic manner, from the structure all the way to the door handles, the colors and the art. Gropius did see a distinction between the artisan and the artist. The same way the artisan would craft a chair with a clear functional goal, emphasized the function of the object, the simplicity of forms, and a lack of extraneous ornamentation or decoration.

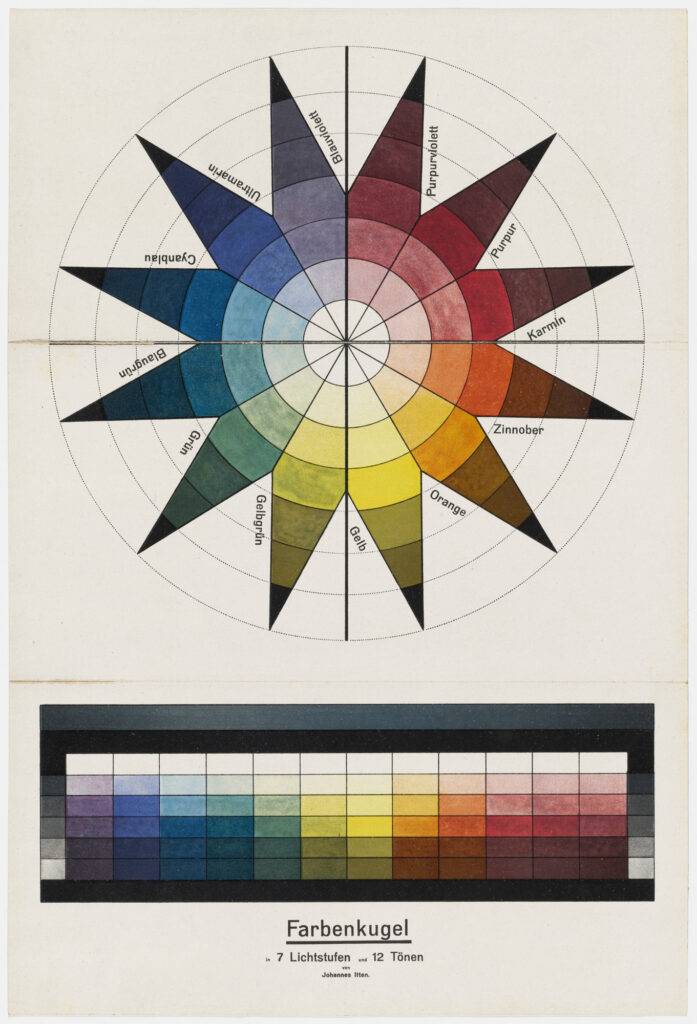

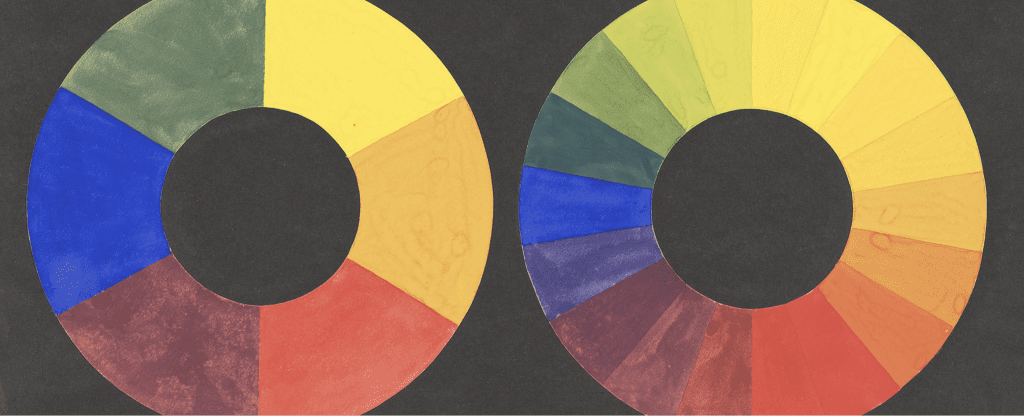

Art was taught at the Bauhaus school with the objective to let students penetrate into the essence of things and understand abstraction; «the Basics of artistic design», which are, in fact, the theory of the design and the famous course on the “Theory of Color”. In this course, artists like Kandinsky taught the theory of color from the history of development of various color systems to modern psychology of perception of color.

The premise of the theory, which was then later developed, lied on the identification and distinction of seven color categories: hue, light-dark, cold-warm, complementary, analogous, saturation, and extension.

Wassily Kandinsky, who pioneered abstract art in the early 20th century, had a rare trait called synaesthesia, which blurs the senses and allowed the Russian painter to associate colours with certain sounds and moods. Red, he heard as a violin; yellow, as a trumpet; and blue, the sound of a heavenly organ.

Furniture design was approached with the same scientific method as art. Teachers at the Bauhaus introduced the distinction between “matter” and “material”. The study of matter consisted of the comparison of different materials relative to each other, whereas the study of materials pertained to the properties of a single material. This approach allowed for the discovery and use of new materials in furniture design, to improve performance, durability and cost.

Can functional Bauhaus design be beautiful?

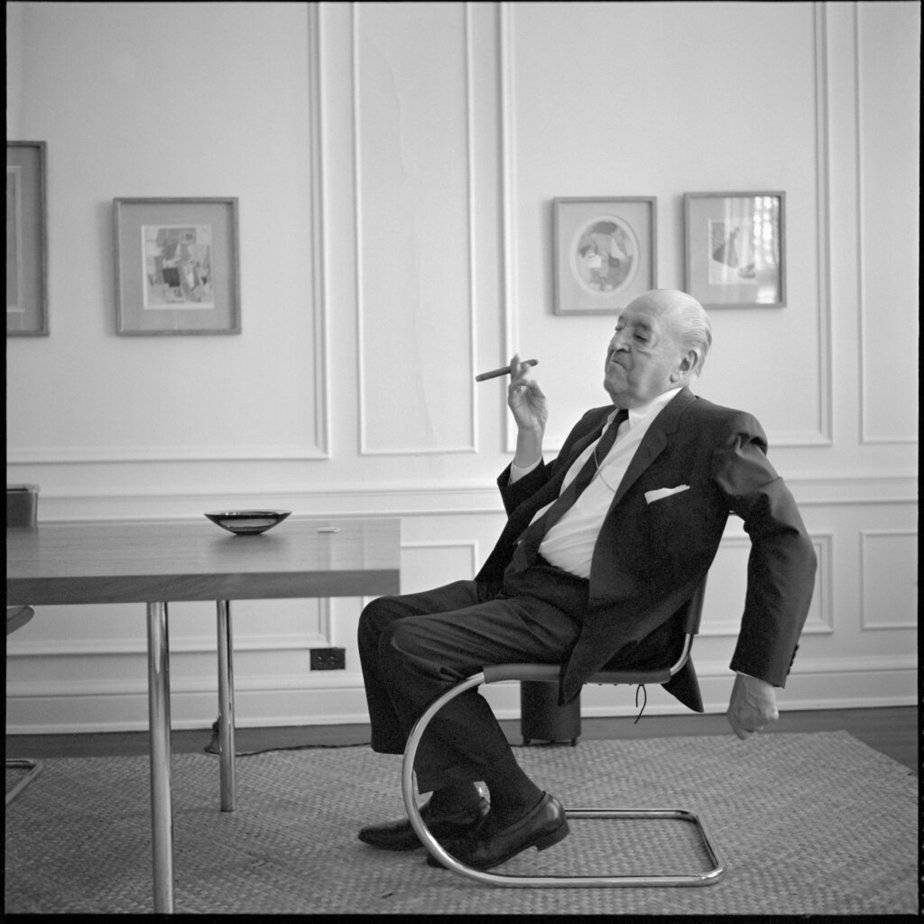

In a lecture given in 1932, the transcription of which appeared in the review Werk (Breuer, 1932), Marcel Breuer attempted to distinguish between modern and fashionable. For the Bauhaus architect and furniture designer, one of the fathers of modernism, the drive for innovation– of the object, of the habitat, of life – drives, under the pressure of logic and of passion, modernism.

Fashionable objects, on the other hand, would be the product of a mood, of a “healthy boredom” which arises from our need for entertainment and variety. To confuse the two would be harmful: the modern movement runs the risk of running out of steam, explains the author, because it will have been defended “with a narrowness of mind which, in order to appear modern at all costs, has succumbed to the allure of fashion “.

Ludwig Mies van der Rohe

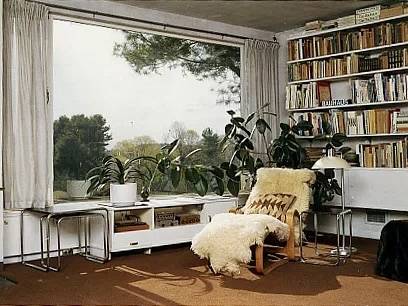

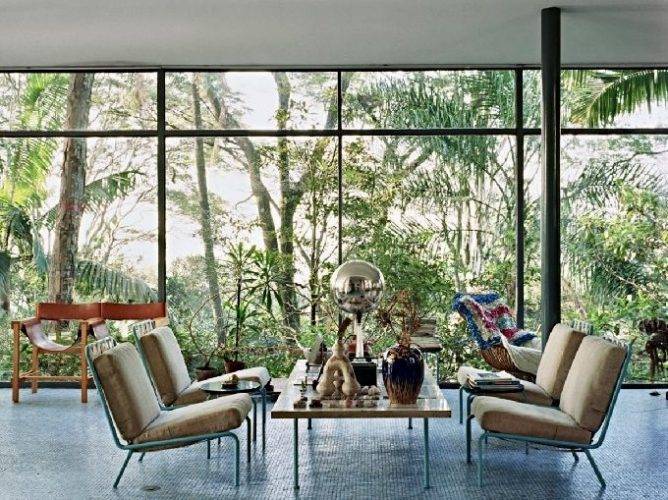

Not all architects shared Breuer’s opinion. Charlotte Perriand, who worked with Le Corbusier, understood that the a home decor should spark joy and happiness. She then coined the expression “fonctionalisme excessif” whereby the quest for the ultimate came at the expense of esthetics. Charlotte Perriand would never have submitted to this excessive functionalism. For her, living should be a pleasure, a celebration renewed every day, and for that it was necessary to have a friendly space.

The male dominated movement became synonymous with austerity. The ideal living space would count the bear minimum. It did however change design for ever.

Our Bauhaus Inspiration Board